HISTORY

Located on the right bank of the Vienne River, the Château des Ormes stands among the grand aristocratic residences of the Ancien Régime and is one of the most remarkable architectural achievements in Touraine and Poitou, from the 18th to the 20th century.

Its renown is inseparable from the Voyer de Paulmy d’Argenson family, an illustrious lineage that owned the estate for over two centuries.

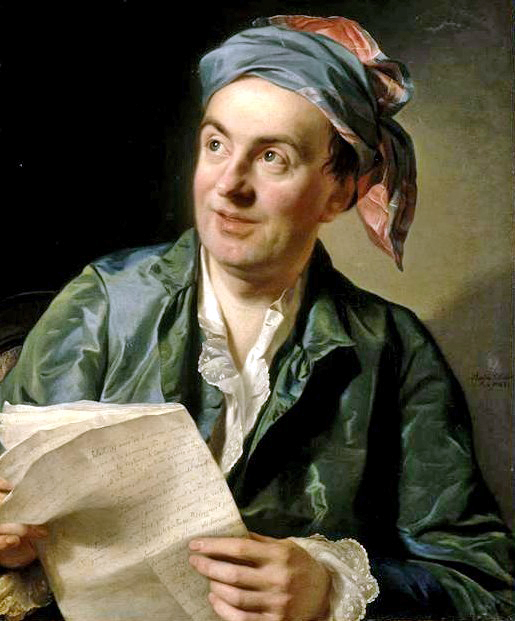

The château also owes its prestige to the great minds it welcomed in the 18th century — Voltaire, Marmontel, Moncrif, and Dom Deschamps — who gathered around Count Marc-Pierre Voyer d’Argenson, Minister of War under Louis XV. Under his patronage, the château became a true intellectual hub known as « The Academy of Les Ormes.

FROM THE ORIGINS TO THE 16TH CENTURY – THE BIRTH OF AN ESTATE

The first records of the Château des Ormes date back to 1460, at the marriage of Guillaume de Marans, squire and lord of Hommes-Saint-Martin and Loubreçay (communes of Bonnes), with Alix-Auguste Aigret, daughter of Jean Aigret, lieutenant at the Châtelet of Paris.

At that time, the site was still a modest seigneurial residence.

The Marans family retained ownership until the early 17th century, laying the foundations for what would become one of the most distinguished estates in the Vienne.

THE 17TH CENTURY – THE RISE OF TO PROMINENCE

In 1608, the seigneury passed into the hands of Jean Elbène, criminal lieutenant of Poitiers, councillor to the Parliament of Brittany, and steward to Queen Marie de Médicis.

Upon his death, the property went to his sister Jeanne, who kept it until 1624.

That same year, the Château des Ormes was purchased by Alexandre Gallard de Béarn, Baron of Saint-Maurice, who owned it until his death in 1637.

Shortly afterwards, in 1642, the estate was acquired by Antoine-Martin Pussort, royal councillor in the King’s Council of State and Privy Council, and at the Cour des Aides.

Uncle to the great minister Colbert, he used his fortune and influence to have the land elevated to a barony in 1652.

A church was then built near the château.

Unmarried and without heirs, Antoine-Martin bequeathed the estate to his brother Henri Pussort, who owned it until his death in 1697.

Like his elder brother, he held high office (Councillor to the Council of Finances, member of the Grand Council, Director-General of Finances).

Under his stewardship, the château took on a new scale, befitting his rank, and already reflected the grandeur and ambition of its future owners — long before the arrival of the d’Argenson family.

THE 18TH CENTURY – THE GOLDEN AGE

At the dawn of the 18th century, the Château des Ormes entered a new era of prosperity.

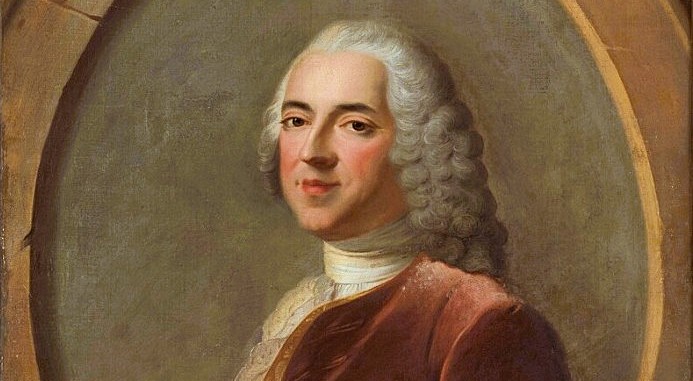

After passing through several hands, it was purchased in 1729 by Marc-Pierre Voyer de Paulmy, Count d’Argenson, Councillor of State and Minister of War under Louis XV.

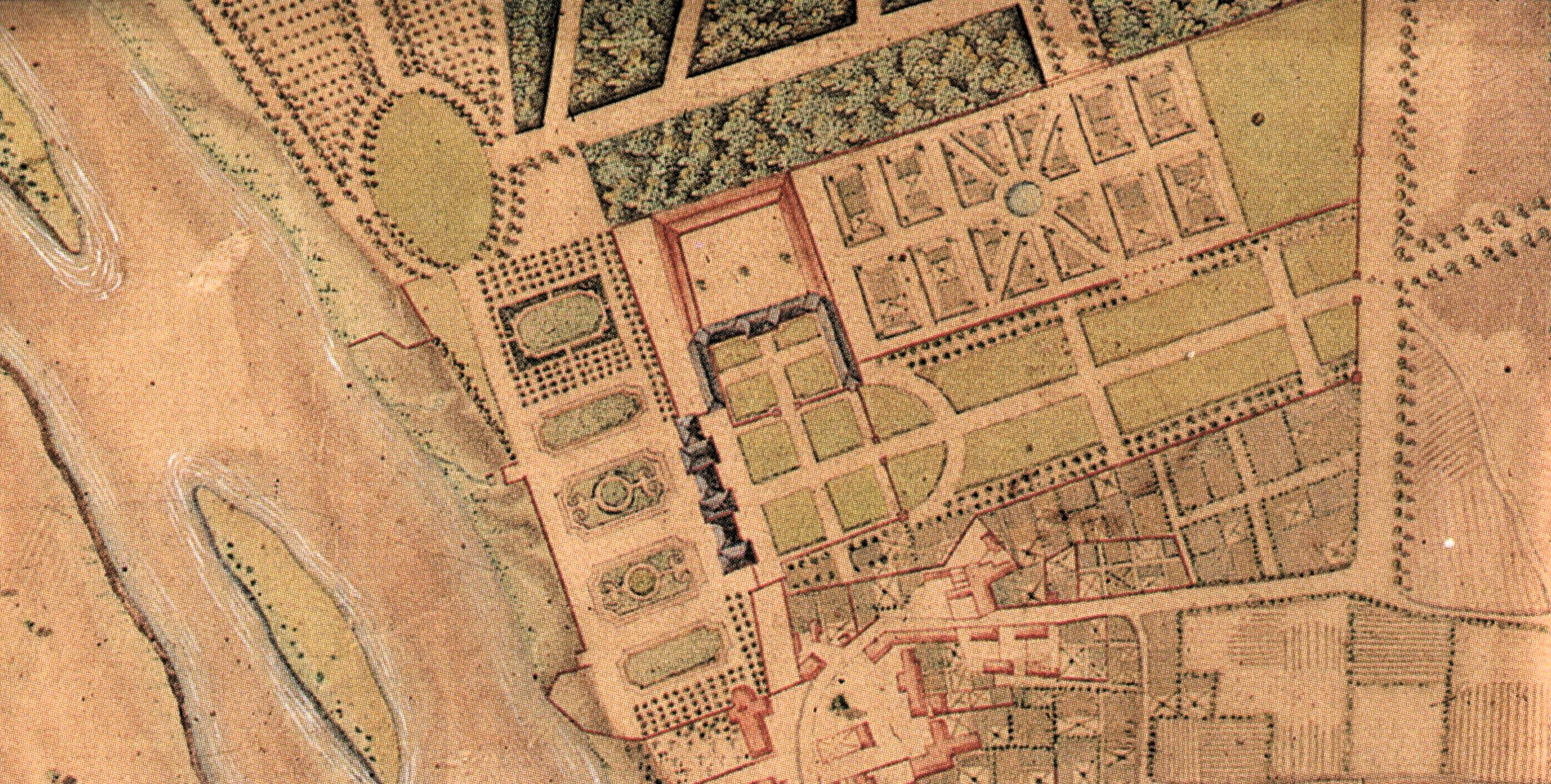

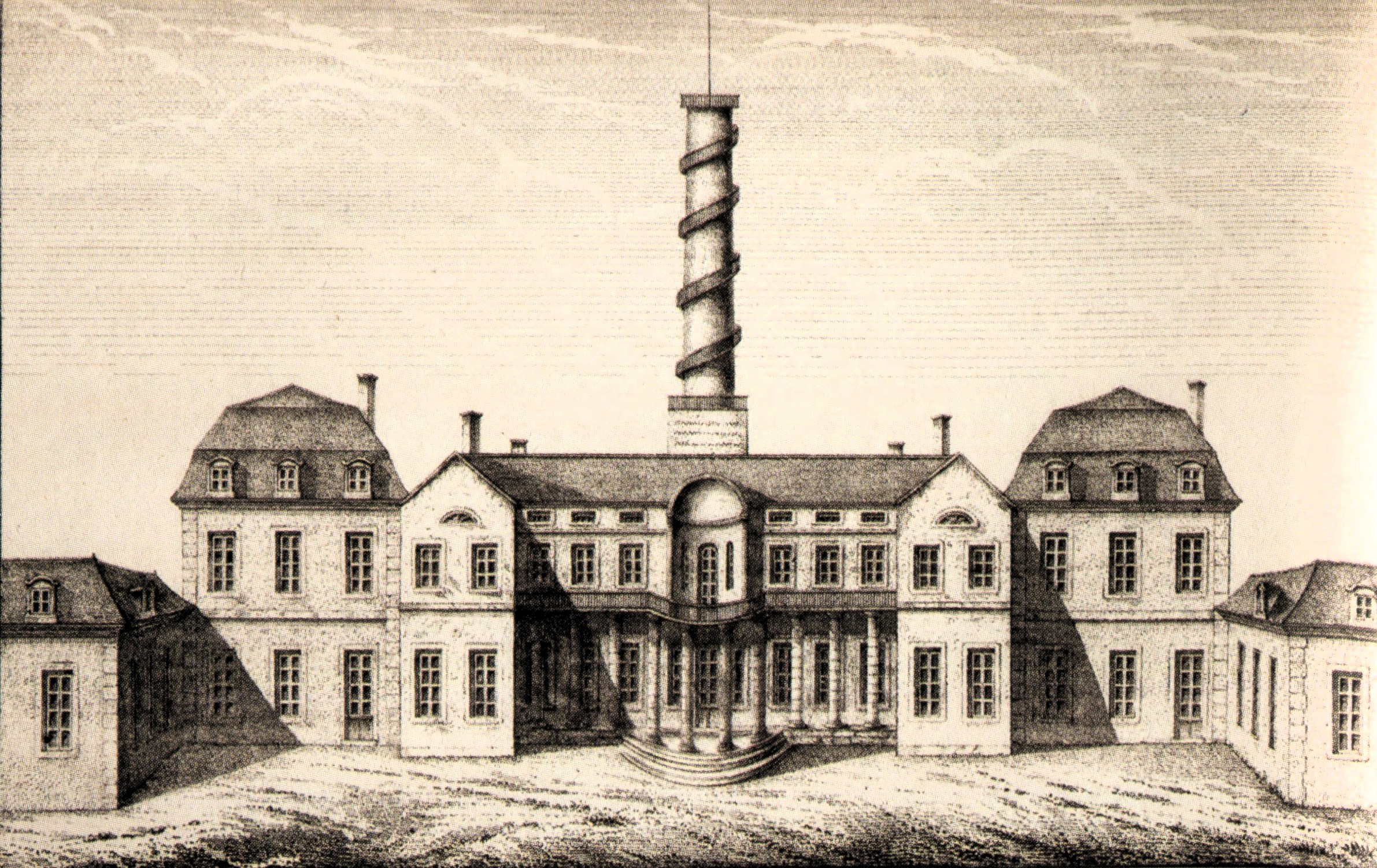

An influential figure and confidant of the Duke of Orléans, he profoundly transformed the estate: expanding its lands, redesigning the park and terraces, building new wings, and embellishing the château.

Between 1757 and 1764, while in exile on his lands, he undertook vast works, spending lavishly to give Les Ormes the grandeur of the finest residences in Touraine.

Under his guidance, the château also became a leading intellectual centre of the Enlightenment.

Its library — one of the richest of its time with over 6,600 volumes — hosted discussions among Voltaire, Marmontel, Moncrif, Fontenelle, President Hénault and Dom Deschamps.

These gatherings formed what became known as “The Academy of Les Ormes,” which made the estate famous far beyond the region.

When he died in 1764, his son Marc-René, Marquis de Voyer, continued and expanded his father’s work.

A passionate horseman, he turned Les Ormes into one of France’s most renowned stud farms, introducing English breeding methods and welcoming princes of the blood — the Count of Artois (future Charles X) and the Duke of Chartres (future Philippe-Égalité).

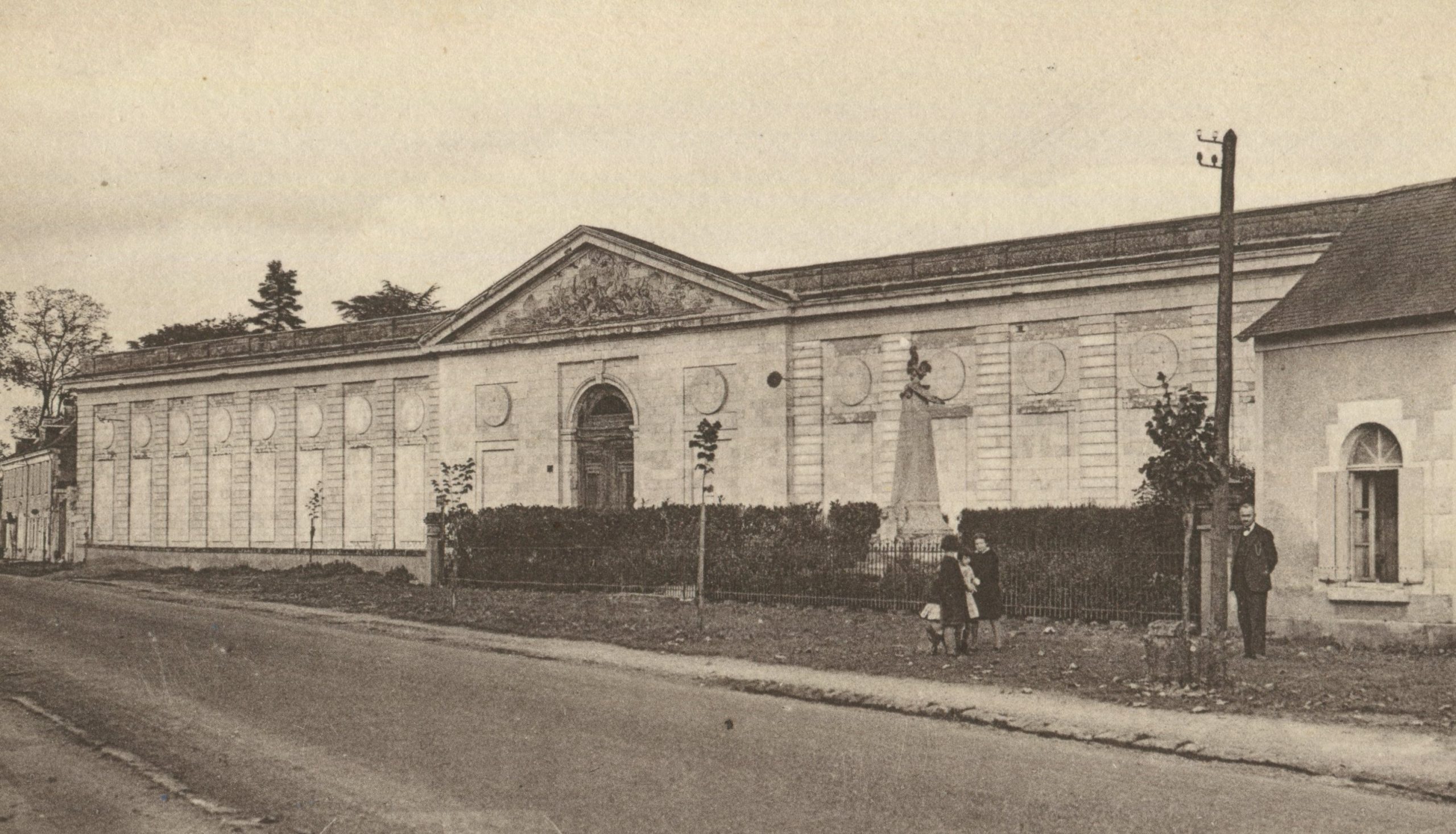

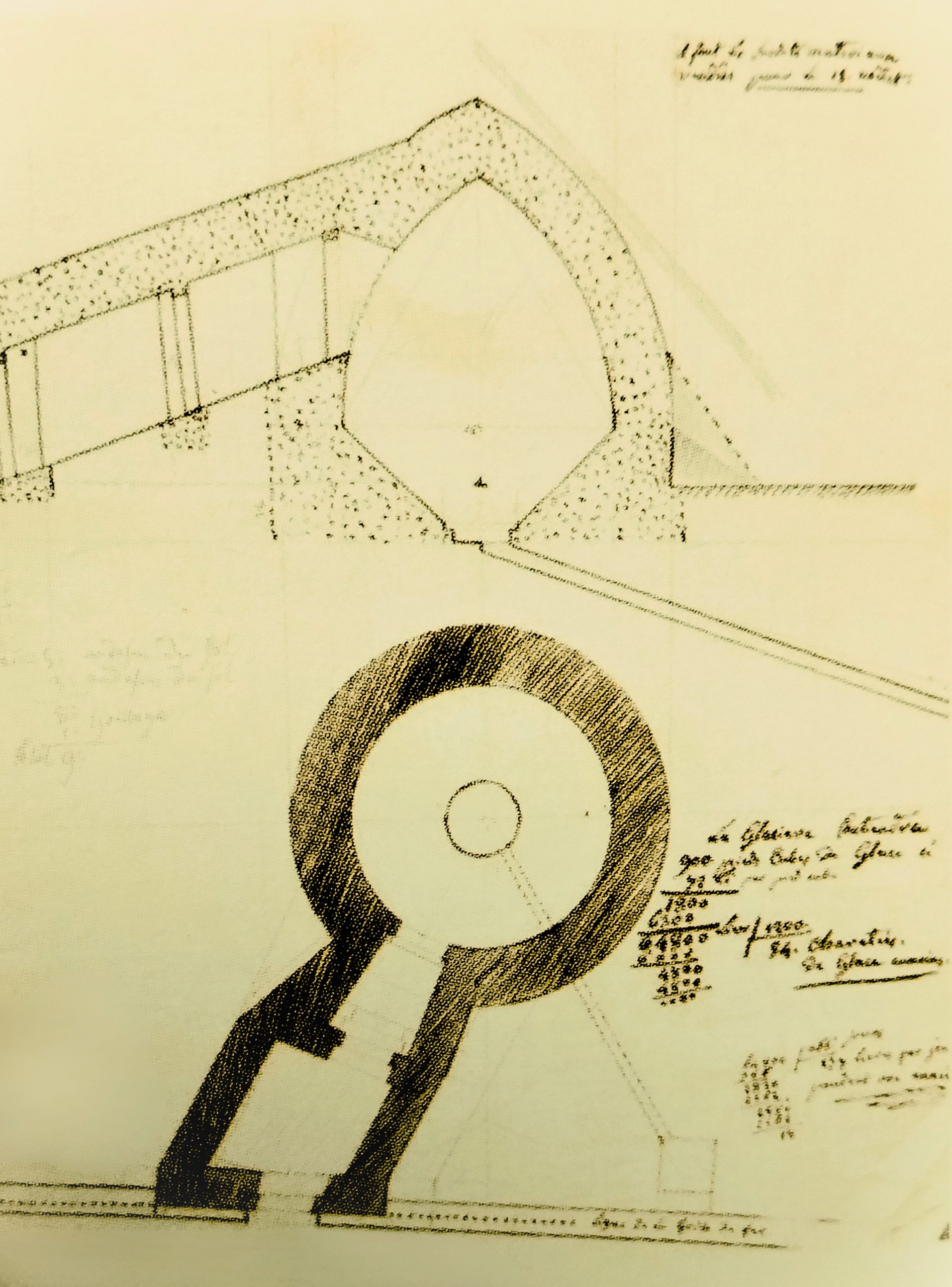

A visionary, he commissioned the architect Charles De Wailly to design ambitious projects: a monumental central building blending antique and modern styles, a barn-stable decorated with sculpted reliefs by Augustin Pajou, and a spectacular staircase and column that remain landmarks of 18th-century French architecture.

By the Marquis’s death in 1782, the estate had reached its zenith.

Though some projects remained unfinished, the Château des Ormes was then regarded as an artistic, intellectual and equestrian landmark — a symbol of the splendour and ambition of the d’Argenson family during the Age of Enlightenment.

THE 19TH CENTURY – DECLINE AND TRANSFORMATIONS

At the beginning of the 19th century, Marc-René-Marie de Voyer de Paulmy, Marquis d’Argenson, active in local and national politics, sought to restore the estate’s former glory.

The library was enlarged and redesigned in 1800–1801, a windmill was built in 1806, and the park on the château side was reshaped in the English landscape style, including the creation of a herbarium and a botanical garden.

Several restorations marked the period (rebuilding of the icehouse, consolidation of the dining room).

But after his resignation in 1813, decline set in: debts accumulated, lands were sold, and the central pavilion was demolished in 1821.

Throughout the century, the estate was gradually divided and sold off in parcels, and the grand landscaping projects remained unfinished.

THE 20TH CENTURY – RENEWAL AND THE DEPARTURE OF THE D’ARGENSON FAMILY

At the turn of the 20th century, a will for renewal emerged.

Between 1903 and 1908, Pierre-Gaston-Marie-Marc, Count d’Argenson and grandson of Marc-René-Marie, rebuilt a central residence inspired by the 18th century, designed by the Parisian architect Alfred Coulomb and adorned with neo-rococo façades.

The château was fitted with modern amenities, including electric lighting in 1906.

However, financial difficulties persisted.

After 1945, the d’Argenson family could no longer maintain the estate, and further sales in the 1960s–1970s fragmented the park.

Shortly after the death of Marquis Charles-Marc-René d’Argenson in 1975, his heirs were forced to sell the château and part of its furnishings.

Thus, the estate left the d’Argenson family, which retained only a small adjoining property.

THE 21ST CENTURY – A NEW RENAISSANCE

After centuries of splendour, decline and renewal, the Château des Ormes has entered a new chapter.

In 2000, it was acquired by a Parisian doctor, Dr Sydney Abbou, who launched an ambitious restoration campaign to revive its former prestige.

Partially listed as a Historic Monument in 1966 and fully listed in 2012, the château is now recognised as one of the heritage jewels of the Vienne.

The award of the Maison des Illustres label further attests to this recognition.

This renaissance is not merely a return to the past: it embodies the estate’s ability to reinvent itself and to reconnect with its history while embracing the 21st century.

Having traversed six centuries of history, the Château des Ormes is no longer just a witness to time — it has once again become a living place of memory and culture.